Nazywam się Raymond Porter. Mam 68 lat. W zeszły wtorek oglądałem, jak spuszczają moją jedyną córkę do zamarzniętej ziemi na cmentarzu Cedar Hill w Minneapolis.

Ziemia była tak twarda, że dźwięczała, jakby nie chciała się otworzyć. Mała papierowa flaga USA – jedna z tych, które wbija się w ziemię w domu pogrzebowym – drżała obok jej imienia, łopocząc na wietrze, jakby rozgniewał się na cały świat. Mój stary pick-up czekał na skraju żwirowego podjazdu, z klapą pokrytą śniegiem, a wyblakły magnes na flagę trzymał się metalu jak obietnica, którą złożyłem dawno temu i której nigdy nie złamałem. Z głośnika czyjegoś telefonu wydobywał się chrapliwy tekst Sinatry – cichy, wręcz obraźliwy – tuż pod głosem księdza.

Stałem tam ze styropianowym kubkiem pełnym letniej kawy, który parzył mi dłoń, a smutek był tak wielki, że moje ramiona wydawały się starsze niż reszta mnie.

Wtedy mój zięć złapał mnie za ramię.

Pochylił się na tyle blisko, że zapach jego drogiej wody kolońskiej przeciął cmentarne powietrze.

„Masz 48 godzin, żeby zabrać swoje rzeczy z domku nad jeziorem” – wyszeptał. „Potem wymienię zamki”.

Uśmiechnął się do mnie. Naprawdę uśmiechał się, jakby właśnie coś wygrał.

I wtedy smutek przerodził się w plan działania.

Nie sprzeciwiałam się. Nie płakałam. Ręce mi się trzęsły, ale nie z zimna i nie tylko z żalu – coś ostrzejszego poruszało się we mnie, coś, czego on nie dostrzegał. Spojrzałam na Dereka Morrisona, mężczyznę, którego moja córka kochała przez piętnaście lat, i powoli skinęłam głową.

„Dobrze, Derek” – powiedziałem. „Rozumiem”.

Zamrugał.

Tego się nie spodziewał.

Czekał na rutynę złamanego staruszka. Błagania. Bałagan. Na moment, w którym będzie mógł udawać szlachetnego przed sąsiadami, wypychając mnie z posesji, którą moja rodzina posiadała od pokoleń.

Nic mu nie dałem.

Odwróciłam się i odeszłam od grobu córki, mijając żałobników, twarze, które patrzyły, jak Sarah dorasta, i wsiadłam do pickupa. Kiedy odjeżdżałam, zobaczyłam Dereka w lusterku wstecznym – czarny płaszcz, markowe okulary przeciwsłoneczne, zaciśnięta szczęka – stojącego tam, jakby wiatr się zmienił i nie wiedział, w jakim kierunku ma potoczyć się jego życie.

Myślał, że odziedziczył wszystko.

Nie miał pojęcia, co zamierzam zabrać.

Zanim opowiem Wam dokładnie, jak to zrobiłam – i co odkryłam, co zmroziło mi krew w żyłach – dajcie znać w komentarzach, skąd oglądacie. A jeśli wierzycie, że cierpliwość i prawda przetrwają chciwość i kłamstwa, polubcie i zasubskrybujcie.

Ponieważ czasami ci, którzy są cisi, nie są cisi, bo są słabi.

Czasami milczą, bo liczą.

Sarah was 44 years old. Healthy. Strong. The kind of woman who ran marathons and still showed up at the community center every Saturday morning to teach yoga like it was a promise she made to the town. She had her mother Martha’s smile and Martha’s stubborn streak—the kind that could carry a family through a bad year without anybody outside the house ever knowing you were struggling.

Three weeks before the funeral, Sarah collapsed in her kitchen.

“Brain aneurysm,” the ER doctor told me at the hospital. “Sudden. Unpredictable. Nothing anyone could have done.”

At first, I believed him.

I wanted to.

You tell yourself a story like that because the alternative is too ugly to hold in your hands.

Derek played the grieving husband perfectly. Black suit. Somber expression. He held Sarah’s hand in the casket like he couldn’t bear to let go.

But I watched him.

I’ve watched people my whole life. Sixty years in construction teaches you to read faces—who cuts corners, who keeps receipts, who smiles while they’re taking from you. Derek’s eyes weren’t wet.

They were calculating.

Every few minutes, he glanced at his phone. Quick little looks like he was waiting for something important to land.

That was the first time I realized the funeral wasn’t his ending.

It was his starting gun.

The reception was at my lakehouse in Wright County—the house Martha and I built thirty-five years ago with our own hands, our own sweat, and the kind of faith you only have when you’re young enough to believe you can hammer your way into a better life.

The place still smelled faintly of pine and old coffee. Sarah’s childhood photos lined the hallway—the missing front tooth, the softball uniform, the prom dress Martha sewed herself because we couldn’t afford the one in the window at Macy’s.

Derek moved through those rooms like he was already measuring them for resale. He poured drinks. He accepted condolences. He kept his hand on the back of Sarah’s favorite chair like it belonged to him now.

I watched him watch the guests.

I watched him watch the money.

And I watched him watch me.

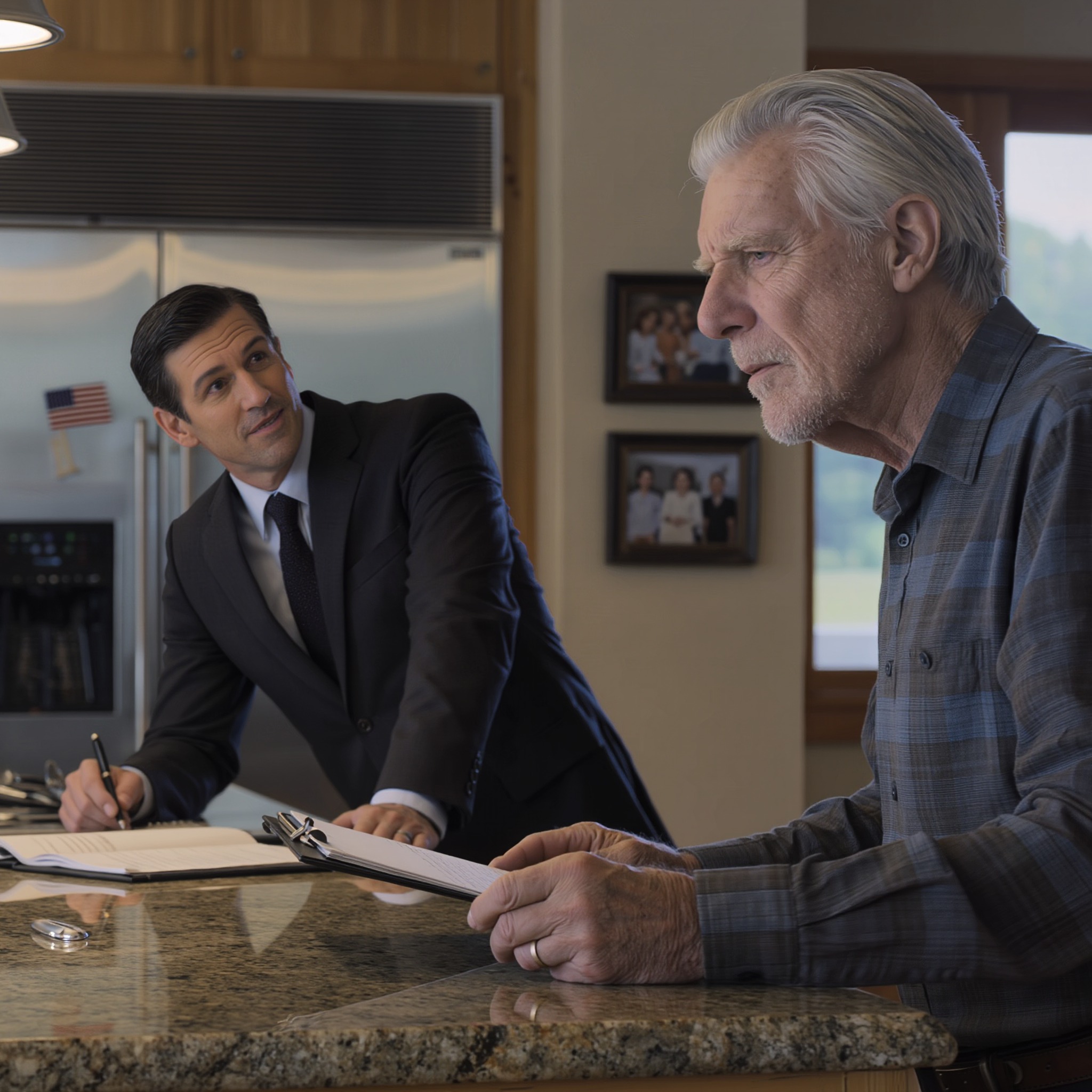

After the last neighbor left, after the casseroles were stacked, after the flowers drooped on the dining room table like tired heads, Derek cornered me in the kitchen.

“Raymond,” he said.

I noticed he didn’t call me Dad anymore. He hadn’t called me Dad in months.

“We need to talk about the property situation.”

“Property situation?” My voice was rough from a whole day of swallowing grief.

He pulled a folder from his briefcase and spread legal documents across my counter like he was dealing cards.

“Sarah signed the lakehouse over to me six months ago,” he said. “Power of attorney. She wanted me to handle the real estate matters. You know how stressed she was about finances.”

I stared down at the bottom line.

My daughter’s signature sat there.

But something in me tightened.

The S in Sarah was too tight. Too controlled. Sarah wrote like she lived—big looping letters, like she was always reaching toward more sky.

“She never mentioned this,” I said quietly.

Derek’s smile tightened.

“Well, she didn’t tell you everything, Raymond. The truth is this house should’ve been in our name years ago. You’ve been living here rent-free using our resources. Sarah was too kind to say anything, but I’m not.”

“Our resources.”

The house I built with my own hands.

The land my father bought in 1952 for $300 and a handshake.

Derek leaned closer, dropping his voice like we were sharing a secret.

“You have 48 hours,” he said. “Get your things. Get out. This is my property now, and I’m selling it.”

“Selling it?”

“The developer from Chicago is offering $2.3 million for the lakefront parcels,” he said, like he couldn’t wait to taste the number. “I’m not losing that deal because you want to sit around feeling sorry for yourself.”

Two point three million dollars.

For three generations of roots.

I should’ve shouted. I should’ve thrown something. I should’ve called him a liar right there in Martha’s kitchen.

Instead, I felt something cold settle into my bones—the same cold I felt twelve years ago when Martha passed and the world kept spinning like it didn’t notice.

“All right, Derek,” I said. “I’ll be out by Thursday.”

He actually laughed.

Just like that.

“No fight,” he said. “Smart. I thought you’d make this difficult.”

“What’s the point?” I made my voice small. Tired. “You have the papers. Sarah signed them. I’m just an old man with nothing.”

Derek patted my shoulder like I was a dog he’d finally trained.

“Smart choice, Raymond,” he said. “My lawyer will send over the formal notice, just to keep everything clean.”

He walked out.

I heard his Mercedes start in the driveway.

I heard the crunch of gravel as he drove away.

And when the taillights disappeared down the road, I stood in my kitchen and let the silence settle.

Then I did something Derek never expected.

I went outside.

The cold slapped my face. My pickup sat where I’d parked it, the faded flag magnet still on the tailgate.

I don’t know why I reached for it. Maybe because my hands needed something to do besides shake. Maybe because that magnet had been there through every election year, every Fourth of July parade, every season Martha and I tried to convince ourselves we were still young.

I peeled it off.

And the second the edge lifted, I saw it.

A thin, folded piece of paper tucked underneath like someone had slipped it there on purpose.

My heart stuttered.

I opened it with fingers that didn’t feel like mine.

The handwriting was Sarah’s.

Big. Loopy. Familiar.

Dad—if anything ever happens and Derek starts talking about “papers,” don’t argue. Don’t fight.

Call Margaret Chen.

Check the lockbox.

Love you.

Below that, in the corner, she’d scribbled one more line like a whisper she didn’t want Derek to overhear:

29 missed calls isn’t an accident.

I stared at that number until my vision blurred.

Bo trzy tygodnie wcześniej, w dniu, w którym Sarah zasłabła, mój telefon leżał na ładowarce po drugiej stronie pokoju, podczas gdy ja piłowałem piłą na budowie dla starego przyjaciela. Wróciłem do niego i zobaczyłem nieodebrane połączenia.

Dwadzieścia dziewięć.

Mówiłam sobie, że Sarah jest niespokojna. Mówiłam sobie, że smutek tworzy schematy z niczego.

Jednak liczba ta nie stanowiła żadnego wzorca.

Yo Make również polubił

Jak pozbyć się śluzu w oskrzelach i gardle? Domowe przepisy z natychmiastowymi efektami

Choroba dziąseł: cichy zabójca, 8 domowych sposobów na jej naturalne wyleczenie

Nie miałem pojęcia, że to możliwe!

W Boże Narodzenie moja mama uśmiechnęła się do mnie przez stół i powiedziała: „Sprzedaliśmy twój pusty dom. I tak nigdy z niego nie korzystasz”. Mój tata siedział tam i liczył pieniądze, jakby to była gra. Ja po prostu popijałem kawę. Później ktoś zapukał do drzwi – dwóch urzędników z mojego wydziału prosiło o rozmowę z „nowymi właścicielami” domu, którego tak naprawdę nigdy nie sprzedali.