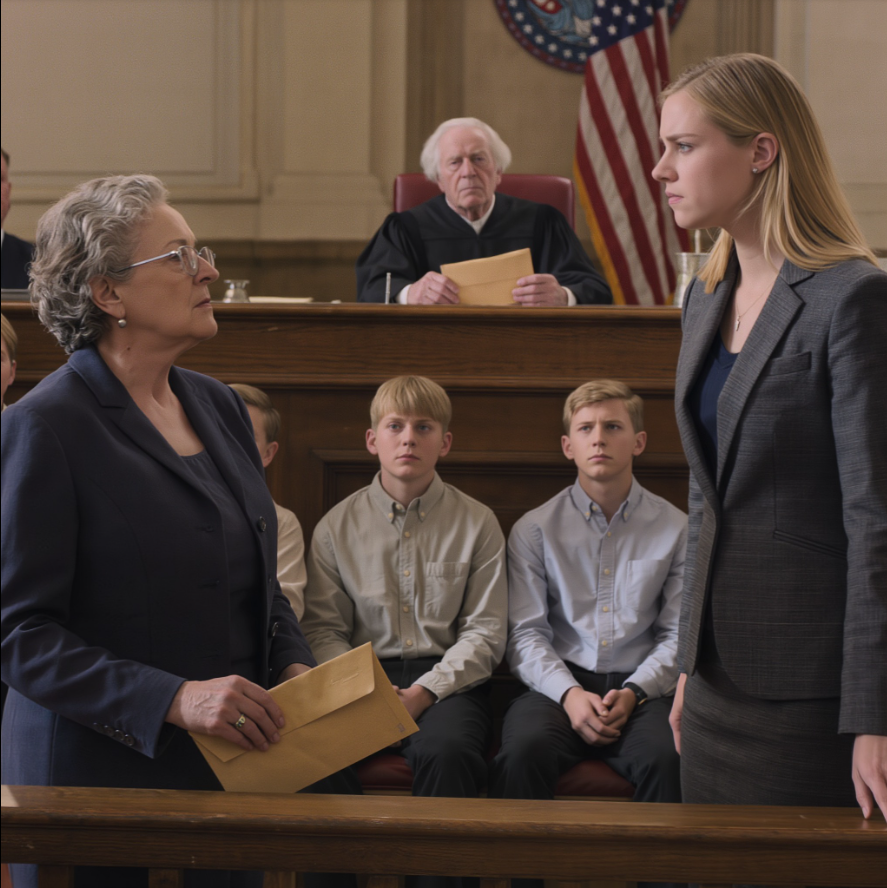

“But…” Daniel continued, glancing back at his brothers. Marcus gave a tiny nod. David stared straight ahead, jaw tight. “But we’d like the chance to try.”

I let out a breath I hadn’t realized I was holding. My heart cracked and swelled at the same time.

The judge studied them for a long moment. “Very well,” he said. “Here is what we’ll do…”

By the end of the hearing, a plan had taken shape: a two-week trial period. The boys would spend alternating days with Rachel in Seattle—supervised at first, then with short unsupervised stretches if things went well. At the end of two weeks, there’d be another hearing. The final decision would take their wishes into strong consideration.

It was, legally speaking, fair.

Fairness and mercy are not always the same thing.

When the gavel finally came down, the courtroom exhaled as one. Papers rustled. The bailiff called the next case. The young reporter scribbled a few last notes and slipped out, already dialing her editor.

I sat for a moment longer, hands resting on the now-almost-empty envelope. Without the documents, it felt strangely light. As if some of the weight I’d been carrying alone had finally moved into the open air.

“Mom?” Daniel said softly.

I looked up at him and saw the three-year-old who’d clung to my leg the first time his mother missed a visit and the seventeen-year-old who’d just told a judge he wanted to try knowing her anyway.

“Let’s go home,” I said.

Outside, the January air bit at my cheeks. The Multnomah County courthouse rose in pale stone behind us, its steps worn smooth by decades of footsteps. The flag out front snapped in the wind, red and white against a low, gray sky. A MAX train glided past with a metallic sigh, carrying people whose lives did not hinge on a judge’s ruling that day.

We walked in silence to the parking lot. My old Honda Civic waited where I’d left it, one hubcap missing, a crack in the windshield shaped like a crooked smile.

Marcus climbed into the front seat, knees up against the glove compartment. The twins wedged themselves in back, shoulders touching, breaths visible in quick little clouds until the heater wheezed to life.

No one spoke until we were halfway home.

“So,” I said finally, because someone had to break the silence, “how are you feeling?”

“Hungry,” David said automatically. It made all three of them snort a little. Relief, leaking out from seams that were too tight.

“Serious, Dave,” Daniel said.

“Scared,” Marcus admitted. “Confused. Hopeful. Guilty. All of it.”

“Guilty?” I asked, flicking on my turn signal.

He stared out his window. “It feels like… like wanting to know her is betraying you.”

“Hey,” I said sharply enough that he flinched. I drew in a breath, softened my tone. “Look at me.”

He turned. I caught his eyes in the rearview mirror, brown and earnest.

“You cannot betray me by wanting your mother,” I said. “You hear me? That’s not how this works.”

“What if we like her?” David asked from the back seat, voice small. “What if she’s… different now?”

“Then I’ll be grateful,” I said. “Because I’ve spent fifteen years wishing she would be.”

They were quiet a moment.

“What if we don’t?” Daniel asked. “What if she’s the same?”

I turned onto our street, the familiar pothole near the corner rattling the car just enough to remind me we were almost home. The three-story brick building where we lived loomed ahead, paint chipped, windows a patchwork of curtains and blinds.

“Then you’ll know,” I said. “And knowing is better than wondering for the next thirty years.”

We climbed the narrow stairs to our second-floor apartment. Someone in 2A was frying onions; the smell seeped under their door. A TV played a game show somewhere above us. Our hallway lights flickered before settling into a steady glow.

Inside, the air held the faint scent of last night’s spaghetti and the cinnamon candle I lit on hard days. The boys kicked off their shoes by habit, scattering them in a messy pile near the door. Backpacks landed with thuds. Marcus headed straight for the kettle. Daniel went to open the blinds. David, of course, veered to the desk where his laptop sat, fingers itching to check something, calculate something, solve something.

“I’ll make cocoa,” I said, shrugging out of my coat. “We have marshmallows. I hid them from Daniel, so there should still be some left.”

He pressed a hand to his chest in mock offense. “Accusations.”

In the kitchen, I reached for the familiar mug with the chipped rim—my favorite, the one with faded blue flowers. The boys’ mugs lined up beside it like a timeline: the green one Daniel had picked at a church rummage sale, the orange one Marcus won at a school carnival, the plain white one David preferred because he said patterns messed with his head.

As the milk warmed on the stove, steam curling up in slow, lazy spirals, I watched my hands shake.

“Grandma, you’re shaking,” Marcus said quietly, coming up behind me.

“I’m fine, sweetheart.”

“No, you’re not,” David said, appearing at my other side, pushing his glasses up his nose.

I set the whisk down. The clink against the pot sounded too loud.

“Okay,” I said. “I’m not.”

We carried the cocoa into the living room. The couch sagged exactly in the spots where three growing boys had flopped for years. The coffee table bore the scars of a thousand homework sessions and one disastrous attempt at home haircuts. On the wall, school photos marched in an uneven line from preschool to eleventh grade.

The envelope lay on the kitchen table where I’d dropped it, deflated and thin. Next to it sat another folder: thicker, newer, edges still sharp. The one the mailman had delivered last month in a plain white envelope marked Important Policy Information Enclosed.

“Boys,” I said, settling into my armchair—the one with the worn arms from all the times I’d gripped them through bad news. “You have questions. Ask them.”

Daniel didn’t hesitate. “Why didn’t you tell us?” he asked, gesturing at the now-empty envelope. “About all of that. About how many times you signed for us. About Mom never being on anything.”

“Because children shouldn’t have to carry their parents’ failures,” I said. “Because loving someone and listing their shortcomings on a spreadsheet are two different tasks, and I wasn’t sure your hearts were ready for the second one while they were still healing from the first.”

“We’re not children anymore,” Marcus said.

I looked at them—broad shoulders, big hands, voices that didn’t squeak when they got excited anymore. Somewhere between second-grade spelling tests and late-night drives to pick them up from shifts at the grocery store, my grandsons had turned into young men.

“No,” I said. “You’re not.”

I stood, walked to the table, and picked up the new folder. Its weight was different from the old envelope’s—less memory, more math. Numbers and signatures. Contingencies and clauses.

“This is your father’s life insurance policy,” I said, returning to my chair. “The one through the Army we never talked much about because talking about it meant admitting he might not come home.”

Daniel’s jaw tightened. I saw the echo of his father there—a man who’d once joked his way through packing a duffel bag because joking was easier than saying goodbye.

“Your father was twenty-eight when he signed this,” I said, opening the folder. “His handwriting was neater than mine. He added you boys as beneficiaries after you were born. Set it up so you couldn’t touch the bulk of it until you turned eighteen.”

“How much?” David asked, voice barely above a whisper.

“Enough,” I said. “Enough to pay for college without loans. Enough to give you each a start in whatever life you choose. Enough that someone might be tempted to reconnect when the payout neared.”

The realization landed in stages across their faces. First confusion. Then dawning understanding. Then hurt.

“She only came back because of the money,” David said.

“We don’t know that for certain,” I said automatically, because I’ve spent a lifetime smoothing edges.

“Yes, we do,” Daniel snapped. Then his shoulders dropped. “Grandma, stop protecting us. Stop protecting her. Please.”

He crossed the room in three long strides and knelt in front of me, his hands closing around mine.

“You’ve carried this alone for too long,” he said. “Let us help.”

My eyes burned. The room blurred.

“Six months ago,” I said, “Rachel filed paperwork to have me declared an unfit guardian.”

All three boys froze.

“She what?” Marcus asked.

“She claimed I’d alienated you from her,” I said. “That I’d blocked her attempts to contact you. That I’d mismanaged funds intended for your care.” My lips twisted. “She didn’t mention that the only funds she ever sent were the fifteen dollars she tucked in your Easter cards that one year.”

“How do you know?” David asked, voice sharp now.

“Because my lawyer showed me the paperwork,” I said. “Your mother needed me declared unfit before you turned eighteen. That way, custody would shift back to her automatically, and as your legal guardian, she’d gain control over your father’s policy.”

Anger moved through them like a wave.

“She tried to have you declared unfit?” Marcus repeated, like the words themselves offended him.

“Yes,” I said. “She did.”

Silence settled heavy.

“Why didn’t you tell us then?” David asked.

“Because I still hoped I was wrong about her,” I said, the truth cutting on its way out. “I hoped there was some explanation that didn’t make her look like the villain of a bad movie. I hoped… maybe she’d back down before you ever had to know.”

“And now?” Daniel asked.

“Now we’re here,” I said. “And you deserve all the information before you decide what kind of relationship you want with her.”

Daniel stood and paced to the window, looking down at the small courtyard where they’d learned to ride bikes between the laundry room and the dumpster. Marcus stared at the folder like he could will the numbers to rearrange into something less ugly. David chewed the inside of his cheek, a habit he’d picked up when he was six and never quite lost.

“Judge gave us a two-week trial,” Daniel said finally. “We go up there, see how it feels, then decide. Right?”

“Yes,” I said.

“And you’ll respect whatever we choose?” Marcus asked, searching my face.

The question hurt more than anything that had come before. It said, in its own way, Do you trust us to choose you?

“Yes,” I said. “Even if it breaks my heart.”

Those two weeks stretched out in my mind like a long, narrow bridge over a canyon. Each board creaked when I stepped on it. The wind picked up under my feet. I walked anyway.

Rachel lived in a glass-and-steel condo tower in Seattle, the kind where the lobby smelled like lemon and fresh flowers every day, not just when someone spilled something. The concierge nodded professionally when we walked in—he knew Rachel by name, greeted her with easy charm. The boys looked around like they’d stepped into a movie set.

There was a fireplace in the lobby. Not a real one, but a gas version with artfully arranged stones. A metal sculpture hung from the ceiling, twisting lazily in the HVAC breeze. People in expensive clothes checked their mail, stopped to chat, carried little dogs in designer carriers.

I watched my grandsons absorb it all—the marble, the security, the quiet—that was so unlike our building where kids thundered up the stairs and Mrs. Landry’s TV was always too loud.

Upstairs, Rachel’s condo was all white and glass and clean lines. Floor-to-ceiling windows looked out over the water. A sleek gray couch sat in the center of the living room like it had never hosted a spill. Throw pillows in matching neutral tones sat at perfect angles.

“This is… nice,” Marcus said politely, fingers hovering near a vase he didn’t quite dare touch.

“It’s home,” Rachel said brightly. “Well, our home. Ours, if you want it to be.”

Her boyfriend—fiancé? Partner? I wasn’t sure which label stuck this week—appeared from the kitchen with a practiced smile and a tray of sparkling water bottles. He wore a watch that probably cost as much as my car. His handshake was firm. His eyes were wrong—assessing, calculating, already factoring my grandsons into some equation that had nothing to do with love.

“We’ve set up rooms for you,” Rachel said, leading them down the hall. “Daniel, you’ll be here. Marcus, you get the one with the desk. David, the one with the bigger closet—figured you’d need the storage for all your gadgets.”

The rooms were beautiful in a catalog sort of way: new comforters, matching lamps, framed abstract art. No school posters. No comics tacked to the wall with tape. No chipped baseball trophies or faded photographs.

“Wow,” David said, because he was seventeen, and the idea of having a whole room to himself for the first time tugged at him even if everything about the situation felt wrong.

Rachel watched his face with hawk precision, filing away every flicker of interest. She was good at that—reading people, bending herself into whatever shape would get her what she wanted.

I stayed for an hour that first day. Long enough to see them relax just a little, accept a slice of pizza, laugh at a joke. Long enough for Rachel to pour herself another glass of whatever sat in the fancy decanter on the counter and call it just a splash.

Then I hugged each boy, one by one, at the door.

“You okay?” I whispered in Daniel’s ear.

“I don’t know yet,” he whispered back. “But I will be.”

He looked taller standing in that hallway. Older. Like someone I was going to have to learn new ways of letting go of, whether I liked it or not.

The elevator doors closed on their faces, and I rode down alone. By the time I reached my car, my hands were shaking so hard I could barely get the key in the ignition.

Two days of back-and-forth visits taught me a few things very quickly.

Rachel was trying. In her way. She cooked sometimes, or at least supervised takeout artfully arranged on plates. She asked questions. She remembered their birthdays, even if she knew more about their zodiac signs than their middle names.

She also drank. Not as much as she used to, according to the stories she told when she forgot I was in the room. But enough that her laugh grew just a shade too loud by nine p.m. and her steps a notch too uneven.

Her partner liked to talk about money. Markets. Investments. Opportunities. He’d ask the boys what they wanted to study and then pivot to potential earnings. “You’re sitting on a golden ticket,” I heard him say once when he thought I wasn’t listening. “College debt-free? You could leverage that into something big.”

Leverage. A word that didn’t belong anywhere near my grandsons.

On the fifth day, while the boys were out with Rachel seeing the aquarium, I sat at my kitchen table with Ms. Peters, my neighbor-turned-attorney. A legal pad sat between us. My old crate of documents rested at her feet, the policy folder on the table.

“She’s not just here for them,” Ms. Peters said, tapping the policy. “She’s here for this.”

“I know,” I said.

The kettle whistled. I poured hot water over tea bags in chipped mugs, the steam fogging my glasses.

“Question is,” Ms. Peters continued, “what do you want to do about it?”

“I want the boys to make their own decision,” I said. “With all the information.”

“And you?” she pressed. “What do you want for you?”

I stared at the steam. “Peace,” I said finally. “I’d like a few years without courtrooms.”

“That might require a preemptive strike,” Ms. Peters said. “Or at least a well-timed reveal.”

Which is how, a week later, I found myself at the Rosewood Café in downtown Portland, waiting for Rachel.

The café was hip and cozy in a way that made me feel both out of place and comforted. Brick walls. A chalkboard menu that changed with the weather. Local art in mismatched frames. A barista in a Mariners cap pulled shots of espresso while a couple argued gently over whether Mount Rainier looked more pink or purple at sunrise.

Rachel arrived in a tailored coat, sunglasses pushed up into her hair. She wrapped both hands around her latte when it came, like she needed the prop. Her manicured nails tapped against the cup.

“You’re painting me as a villain,” she said softly, not bothering with small talk. “In court. With the boys.”

“I’m letting the paperwork speak,” I said. “You wrote most of it.”

She rolled her eyes. “People get lost, Mom. They spiral. They make bad choices. That doesn’t mean they’re beyond redemption.”

“Lost people ask for directions,” I said. “You just burned the map and hoped no one would notice.”

Her jaw tightened. “They said they want to try,” she said. “They told the judge. They told me. They’re willing to move.”

“They said they’re willing to get to know you,” I corrected. “That’s not the same thing as uprooting their lives three months before graduation.”

“They’ll be eighteen soon anyway,” she said. “Why are you clinging so hard?”

Because I’ve already lost one child, I thought. I’m not eager to lose three more.

Out loud, I said, “Because someone has to make decisions that aren’t based on panic or money.”

Her eyes flashed. “You think I’m here for the money.”

“I know why you filed to have me declared unfit,” I said. I opened my purse and slid a thin folder across the table. “I also know your partner’s investment firm is under federal investigation. Assets frozen. The file is public record.”

Color drained from her face. “You hired someone.”

“Yes,” I said. “A licensed investigator. With my last thousand dollars.”

“Mom,” she said, voice dropping. “Even if some of that is true—”

“All of it is true,” I said calmly. “Bankruptcy filings. Court dates. The works. And the timing? The week you filed to remove me as guardian is the same week your partner’s assets froze.”

She looked down at the papers, then back up at me. For the first time in a long time, she dropped the act completely. No tears. No excuses. Just raw calculation.

“What do you want?” she asked.

“I want you to withdraw your custody petition,” I said. “Leave the boys here. Let them finish high school in peace. Let them decide if they want to maintain a relationship with you on their terms, not as leverage in some financial strategy.”

“And if I don’t?” she asked.

“Then all of this,” I said, tapping the folder, “goes into the court record. No editorializing. No name-calling. Just dates, documents, and a trail of choices.”

She laughed once, harshly. “You always did think goodness was a finish line you could cross with small chores.”

“No,” I said. “I think goodness is the small chores. Show up. Pay attention. Tell the truth even when it’s inconvenient.”

She stared at me for a long time. Around us, the café buzzed. A toddler dropped a muffin, and his dad swooped in with exaggerated horror. The barista called out “oat milk latte!” like a game show host.

“You can’t keep them from me forever,” Rachel said finally. “They’re my children too.”

“I’m not trying to,” I said. “I’m asking you to stop trying to own them.”

We left it there.

The call came at 6:47 the next morning.

“Mrs. Brown,” the voice on the other end said, clipped and professional. “This is Detective Sarah Martinez with Seattle PD. I’m calling about your daughter, Rachel Brown Hastings.”

My whole body went cold. “Is she…” The word dead stuck in my throat.

“She’s in custody,” the detective said. “She was arrested last night in connection with an ongoing federal investigation into her partner’s investment firm. Wire fraud, conspiracy, a few related charges. She asked that we inform you and provide her attorney’s contact information.”

My knees felt weak. I sank into a kitchen chair.

“Thank you for calling,” I said. It came out on autopilot. Years of politeness, even in the face of disaster.

“Ma’am,” the detective added, her voice softening, “there are three framed photos on the dresser we inventoried. All of them of three boys at different ages. Same frames. Same dust. Looks like they’ve been there a long time.”

A tiny, painful hope pinched my chest. “Thank you for telling me that,” I said.

“She also asked us to tell you she’s willing to sign custody papers in exchange for legal help,” the detective added. “I’m just passing the message.”

“Understood,” I said. “Detective, my daughter and I… we’re not close. I won’t be contacting her attorney.”

“That’s your right,” she said gently. “Good luck, ma’am.”

After I hung up, I stood at the window for a long time, staring at the thin slice of gray sky visible between our building and the next. The courtyard below was empty—bikes chained to the fence, a stray grocery cart someone had pushed up too far. A soda can rolled lazily in the breeze.

Behind me, the boys were getting ready for school—showers running, drawers slamming, the rustle of clothes. Normal sounds. Ordinary life.

“Boys?” I called, my voice strange in my own ears. “Can you come out here?”

They emerged one by one, hair damp, backpacks half-zipped.

“What’s up?” Daniel asked.

“Sit,” I said.

They sat.

“Your mother was arrested last night,” I said. No preamble. I’d learned by now that ripping the bandage off hurts less than peeling it slowly. “Financial crimes connected to her partner’s firm.”

Marcus’s hand flew to his mouth. David’s eyes widened. Daniel just went very, very still.

“Is she… going to prison?” David asked.

“I don’t know,” I said honestly. “Probably. These things can take a while. There’ll be hearings, negotiations, all of that. But it doesn’t look good.”

“What happens to us?” Marcus asked.

“Nothing changes,” I said. “You’re seventeen. You live here. You finish school. You go to college. You keep your lives. This doesn’t change who you are.”

“She wanted us to move there,” Marcus said softly. “To Seattle.”

“She wanted access,” Daniel said. His voice was hard in a way that made my heart hurt. “We were the key.”

I winced at the accuracy. “She’s asked me to pay for her lawyer in exchange for signing custody papers,” I said. “She wants to trade parental rights for legal fees.”

“Of course she does,” David muttered.

“What are you going to do?” Daniel asked.

I reached into the drawer of the side table, pulled out a paper Ms. Peters and I had drafted—a formal letter declining any financial responsibility for Rachel’s legal troubles and itemizing the costs I’d borne raising her children.

“I’m going to send this,” I said. “Wishing her due process. And stepping back.”

They exchanged one of those wordless looks they’d perfected over years of shared rooms and whispered conversations. Then, together, they nodded.

“We’re not going to school today,” Daniel said suddenly.

“You’re what?” I asked.

“We’re staying home,” he said. “We’re not doing whispers and stares and ‘I saw your mom on the news’ today. We’ll do our work from here. We’ll… we’ll talk. We need time.”

For once, I didn’t argue.

“Okay,” I said. “Then we make the day count. College applications. Scholarship essays. Looking at dorms. Plans.”

David sat up straighter. “Plans,” he repeated. Planning calmed him. Numbers were safe.

“What happens when we turn eighteen?” Marcus asked. “With Dad’s policy.”

“It becomes yours,” I said. “All of it. Your father intended that money for your education and your start in life. No court can change his original beneficiary structure now that you’re this close to eighteen—not with the investigation going on, not with the paper trail we have.”

“She can’t touch it?” David asked.

“No,” I said. For the first time in months, the word felt solid. “She can’t.”

Daniel let out a breath that sounded like a weight leaving his chest.

“Then we’ll make sure it does what he wanted,” he said. “No gambling. No stupid cars. Just… the life he hoped for.”

Six months later, I stood in a federal courthouse corridor in Seattle watching through reinforced glass as Rachel was led away.

Federal buildings hum at a different pitch than county courthouses. The ceilings are higher. The lighting is better. The security is tighter. Justice, at that level, wears a suit you can’t buy off the rack.

Rachel’s hair had grown out a bit, the glossy salon waves replaced by a simpler ponytail. The orange jumpsuit didn’t flatter anyone, but she wore it with the same ramrod posture she’d had as a girl when she balanced books on her head for fun. She looked smaller somehow. Or maybe it was just that I’d finally stopped seeing her through the magnifying glass of my own guilt.

She searched my face as the marshal guided her past. For a heartbeat, our eyes met. I couldn’t give her what she wanted—absolution, or outrage, or a promise I’d fix this. I gave her something else instead: a steady gaze that said, You did this. You can survive it. Stand up straight.

A reporter approached as I stepped outside, microphone extended. “Mrs. Brown,” she said, “how do you feel about your daughter’s conviction?”

The sky was low and gray. The air smelled like rain and exhaust. Somewhere across town, my boys—men now—were sitting in college lecture halls, taking notes on subjects I’d never studied, building lives that had nothing to do with fraud.

“Accountability,” I said, looking straight into the camera, “is rarely satisfying. But it’s necessary.”

The clip ended up on the local news that night. I didn’t see it. But a neighbor stopped me in the lobby a few days later and said, “You said what I’ve been trying to say about my own son for years. Thank you.”

The boys left for college that fall in three different directions.

Daniel chose Northwestern, his acceptance letter a small miracle we celebrated with takeout Chinese and a cheap bottle of sparkling cider. He wanted to study journalism. “I want to expose the truth,” he said. “Like you did.”

Marcus headed to Stanford on a need-based scholarship and what his guidance counselor called a “remarkable personal statement.” He wanted pre-med. “If I can fix one heart attack before it happens,” he said, “all those nights watching Grandpa cough will be worth something.”

David landed at MIT, where he disappeared joyfully into circuits and code. “Someone’s gotta build the future,” he said, eyes bright.

We shopped thrift stores for dorm supplies, crammed suitcases into the trunk of my increasingly unreliable Honda, drove up and down the coast. Dropping each of them off felt like leaving a piece of my own body behind, but it was a good kind of ache—the kind you get from stretching in the right direction.

A month into their first semester, a different car pulled into our building’s parking lot. A used Subaru, silver, with fewer miles and no mysterious clunking sounds.

“This is for you,” Daniel said when they all came home for a long weekend and handed me the keys.

“I can’t—” I began.

“You can,” Marcus said. “We figured out the numbers. Used part of Dad’s policy. We’re fine, Grandma. This is so you don’t break down on I-5 in the rain.”

“You’ve given us everything,” David added. “Let us give you a safe car.”

I cried in the driver’s seat while they pretended not to see.

It was Daniel who first floated the idea of buying a house.

Yo Make również polubił

Robisz to źle. Tutaj możesz dowiedzieć się, jaki nawóz jest odpowiedni dla poszczególnych roślin domowych.

Przywróć siłę swoim nogom! 3 naturalne napoje, które dodadzą Ci energii.

Ulepsz swoją poranną kawę, aby przyspieszyć spalanie tłuszczu

10+ ostrzegawczych sygnałów, że twoje ciało potrzebuje pomocy