The now-familiar buzz in my thighs flared to life. My knees trembled.

One inch. Two.

And then I was up.

Standing.

Not straight as a soldier. Not easy. Both hands braced on the bench, back hunched slightly, legs shaking. But up.

The room went absolutely still. You could have heard the lake wind against the windows.

From my new vantage point, everything looked different. I’d forgotten how high that bench really was. How small everyone looked from up here.

I glanced toward the gallery.

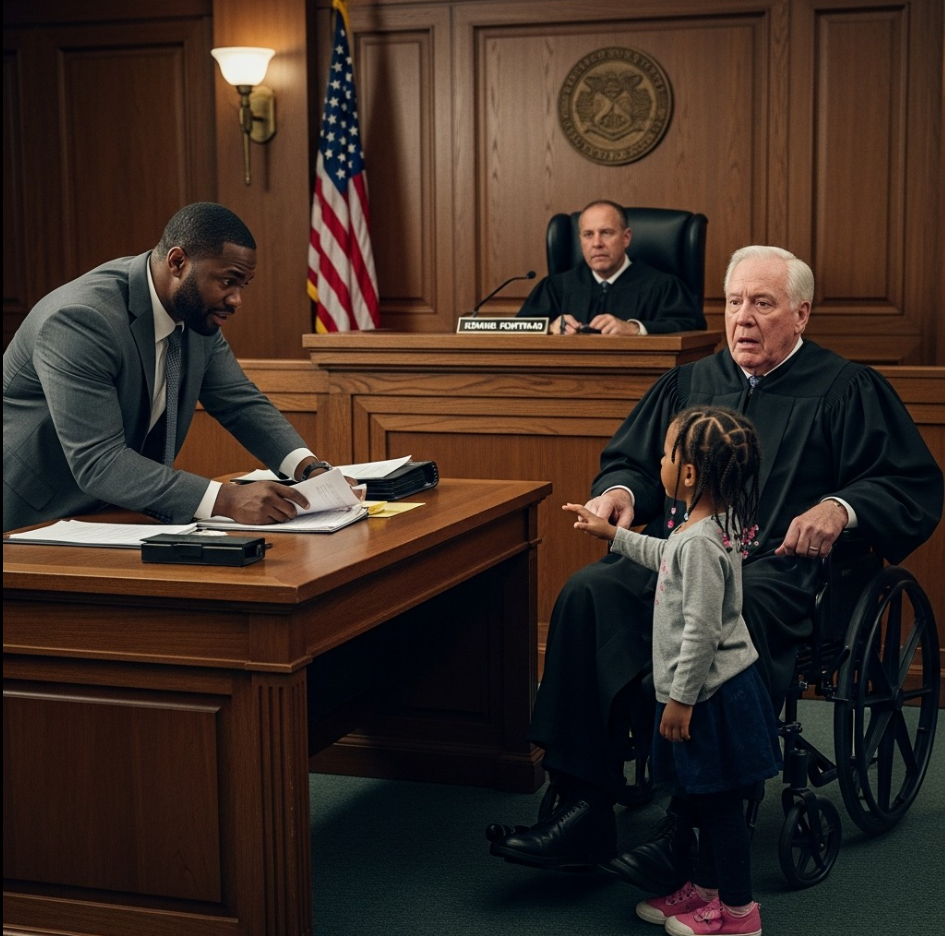

Hope stood on her seat now, hands over her mouth, eyes huge. Darius had both hands pressed flat against the back of the pew in front of him, like he needed something solid to hang on to.

After five seconds—maybe eight—my body demanded mercy. I lowered myself back into the chair, breath coming fast.

Then the courtroom erupted into applause.

It was wildly inappropriate. I should have banged the gavel and barked “Order!”

Instead, I let it happen for a few seconds before lifting a hand. “All right,” I said. “That’s enough. This is still a court of law, not a Cavaliers game.”

The clapping died down, replaced by a ripple of embarrassed laughter.

I looked at Hope.

“Looks like the deal’s paying off,” I said.

She shook her head, braids bouncing. “No,” she called out. “You did that. I just talked.”

Talking, I thought, had done a lot more than people gave it credit for.

I cleared my throat.

“In my years on this bench,” I said, “I have believed that justice meant holding a hard line and never flinching. I still believe that lines matter. Some things deserve firm consequences. But I’ve learned, late and not without some kicking and screaming, that justice without mercy is just punishment in a fancy suit.”

I let that sit.

“This court will still be tough,” I said. “But it will make more room for the possibility that people can change. I have proof of that in my own spine. And in the people sitting in this room.”

We went back to work. There were more cases to hear, more lives to weigh. The news eventually got out—there were cell phones in the gallery, of course—but the story that spread wasn’t “judge stands up.” It was “judge softens, just a little.”

I could live with that.

Years slid by, measured in dockets, holidays, and the slow creep of snow up the sides of the Justice Center steps every winter.

I kept going to rehab. My progress was not a straight line. Some weeks I stood longer. Some weeks pain flared and I swore louder. I graduated from parallel bars to a walker, then to a cane for short distances. The wheelchair stayed, especially on long days in court. But the fact that I had options was its own kind of miracle.

Hope grew.

The next time I saw her in that striped dress, she was a head taller. Then she was in middle school, rolling her eyes at the world like any teenager, but still waving at me when she spotted me at community events.

Darius kept his end of the bargain too.

He showed up, three years into his probation, with a folder of certificates and letters.

“Your Honor,” his lawyer said, “Mr. Moore has completed his community service and is requesting early termination of probation.”

Inside the folder: glowing notes from the legal aid office where he’d helped people read foreclosure papers instead of altering them. Letters from families who’d kept their homes because he’d translated legalese into plain English for them. A picture of him onstage at some community forum, talking about “lessons learned.”

I granted it.

When he shook my hand afterward, his grip was firm. “I tell people where I go that you gave me my life back,” he said.

“No,” I said. “Your daughter did. I just stopped long enough to listen.”

He smiled. “We both know it was more than that,” he said.

Maybe it was. Maybe it wasn’t. Either way, I slept better knowing one less man was carrying a number he didn’t deserve for the rest of his life.

I retired at seventy-two, five years after Hope first marched into my courtroom and knocked a hole in my armor.

Mandatory retirement, some grumbled. “He’s still got it,” others said.

I knew the truth. I had done enough. My body was tired. My mind was sharp, but my patience for politics was thinner than ever. It was time to let someone else sit under the weight of that robe.

On my last day, the courtroom was standing-room only. Lawyers in suits I’d seen for decades. Younger attorneys who’d clerked for me and gone on to build their own careers. Court staff. Cops. A few people whose names I recognized from old case files, now dressed in neat clothes, sitting in the gallery not as defendants but as citizens who wanted to say goodbye.

And on the second row, in a blue blouse and black slacks, was Hope. Sixteen now. Braids replaced by a ponytail. Taller than her grandmother. Darius beside her, tie slightly crooked.

When the speeches were over—some heartfelt, some long-winded, one mercifully short—we had a reception with sheet cake and coffee in foam cups in the jury room. People slapped my back. Told me stories from cases I barely remembered. Asked what I planned to do with my time.

“Annoy physical therapists,” I said. “And maybe learn how to cook something besides scrambled eggs.”

At the end of it all, Hope came to stand in front of me one more time.

“Judge,” she said.

“Hope,” I said. “Or do I have to call you Miss Moore now?”

She smirked. “Only if I have to call you Mr. Callahan,” she said.

“Let’s not,” I said.

She glanced at my cane, standing propped against the table. “You don’t use the chair all the time anymore,” she said.

“Not inside buildings that don’t require me to move like a bat out of hell,” I said. “I still need it a lot. But this”—I tapped the cane—“has earned its keep.”

She nodded slowly. “Do you ever wish it never happened?” she asked. “The car crash. All of it.”

The room had mostly emptied. Diane hovered by the door, pretending not to listen.

“Every day,” I said honestly. “I wish Laura were still here. I wish I’d taken a different route that night. I wish a man hadn’t decided to drink and drive. If I could change that, I would.”

She studied my face. “But?” she prompted.

“But,” I said, “if none of that had happened, I might have stayed the same man I was before. A man who thought justice meant never letting anything soften him. A man who didn’t realize how many people came into that room already broken in places I couldn’t see.”

I thought of all the faces, all the files, all the stories I’d read too quickly in my early years on the bench.

“Terrible things happen,” I said slowly. “We don’t get to dress them up and call them good. But sometimes, if we’re lucky or stubborn enough, something decent grows around them. New habits. New choices. New ways of seeing.”

She chewed on that. “My dad says God doesn’t make the bad stuff,” she said. “He just doesn’t waste it.”

I smiled. “Your father is a wise man,” I said. “You should listen to him.”

“I do,” she said. “Sometimes.”

We both laughed.

“Thank you,” she added quietly. “For my dad. For trying. For… not staying mad forever.”

“I should be thanking you,” I said. “You walked into my courtroom and offered me an impossible bargain. You reminded me that hope isn’t childish. It’s contagious.”

She lifted her chin. “I still would’ve given you my legs,” she said.

“I know,” I said. “That’s what scared me. And what saved me.”

When I left the Justice Center for the last time, I did so on my feet.

Not with a young man’s stride. My gait was slow, careful. The cane clicked on the polished stone. The automatic doors whooshed open, letting in a blast of cold air off Lake Erie.

Murphy held the door. “Take care of yourself, Judge,” he said.

“You too, Murphy,” I said. “Keep those kids in line.”

“Which ones?” he asked. “The defendants or the lawyers?”

“Both,” I said.

Outside, the sky was the pale blue Cleveland only gets on clear winter days. I turned to look up at the tall glass and concrete of the Justice Center. Somewhere up there, Courtroom 12B sat waiting for the next judge to inherit its echo.

For a long moment, the weight of thirty years pressed down on me. All the sentences. All the people. All the days I thought I knew exactly what justice meant, and all the days I wasn’t so sure.

Then a gust of wind off the lake made my coat flap. My legs wobbled a little. I shifted my weight, found my balance, and took a step.

One step. Then another.

Every stride hurt, just a little. Every stride also felt like a decision.

I thought of all the men I’d sent to prison to pay for what they’d done. Some of them had needed it. Some of them had deserved every day. Some, I now believed, could have used a judge who knew how to bend before he broke them.

I couldn’t go back and rewrite their stories.

But in my own, late chapter, I had learned something I wished I’d known sooner:

Sometimes the bravest thing a man in a robe can do is let a small child’s voice in the back row change the way he sees the world.

The miracle, in the end, wasn’t that I learned to stand again.

It was that I finally learned how to sit in judgment without forgetting what it feels like to fall.

Yo Make również polubił

Ciasto Filadelfia z Malinami

Wiśniowa Poezja – Pyszne Ciasto

Porada kominiarza, jak utrzymać ogień w kominie PRZEZ CAŁĄ NOC.

Wczoraj w naszym domu pieczenie ciasteczek zostało zastąpione tym luksusowym ciastem kokosowym, które rozpływa się na języku