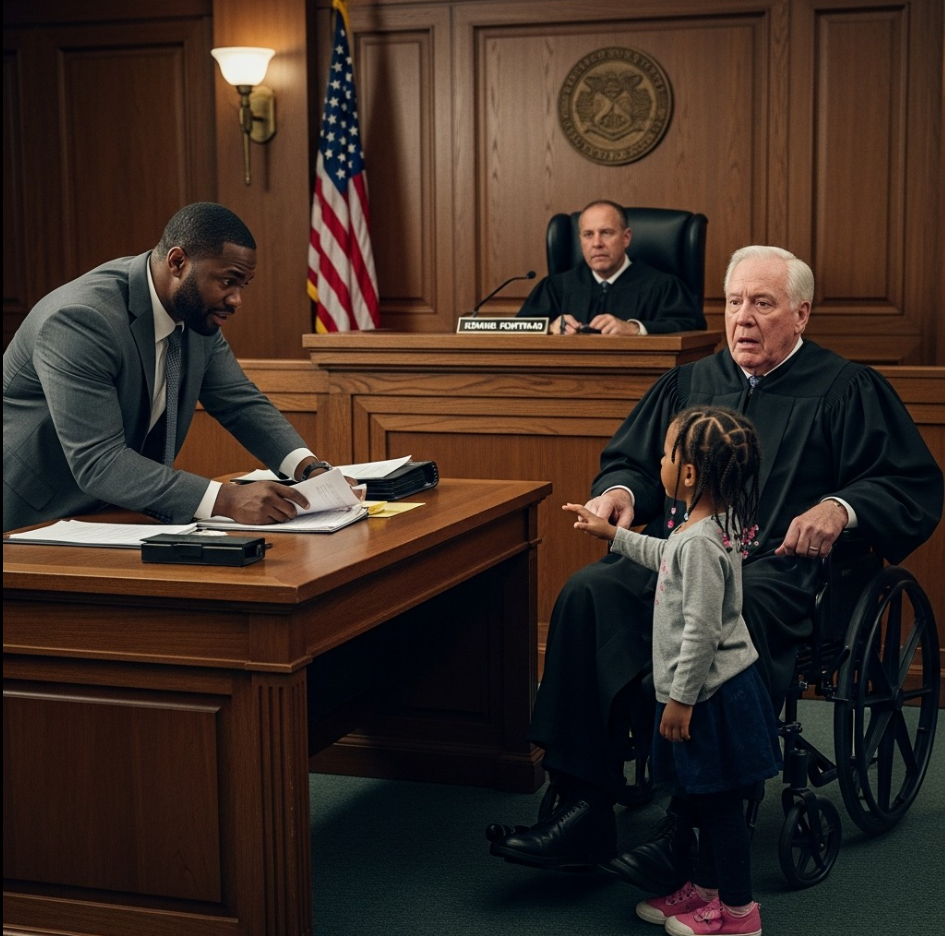

Then she tipped her small head back, met my eyes over the high oak of the bench, and said, clear as a bell, “Your Honor, if you let my daddy go, I’ll give you my legs so you can walk again.”

Laughter flickered through the courtroom like static. A juror smiled, embarrassed. The prosecutor rolled his eyes. My clerk, Diane, froze with her fingers hovering over her keyboard. Even the bailiff’s stern face twitched.

I didn’t laugh.

Because ten years earlier, on a rain-slick stretch of I-90, a drunk driver had crossed three lanes of traffic and turned my life into a before and after. Before: a wife, a body that worked, a restless middle-aged judge who still believed hard work could fix just about anything. After: my wife, Laura, in the ground at Holy Cross Cemetery, and my legs as useless as the prayers people whispered over my hospital bed.

My name is Judge Raymond Callahan. I’m sixty-seven years old, and for the last ten of those years I’ve rolled into the Cuyahoga County Justice Center in a wheelchair, past the security scanners, under the carved stone seal of Ohio, through hallways that smell like old paper, coffee, and human trouble.

I built a reputation the way other men build a house—brick by brick, case by case. “Tough but fair,” the Plain Dealer called me once in a profile that used a photograph of me looking stern in front of the courthouse steps. Politicians liked to stand next to me in campaign mailers. Defense attorneys nudged their clients and whispered, “If you get Callahan, you better be ready.”

I told myself I was doing what the law required. I told myself being unmoved made me objective. After the accident, after Laura, after the surgeries and the rehab and the lonely nights, that hardness became a habit. Feelings didn’t fix broken spines or bring back the dead. The law was what I had left.

And then they brought in Darius Moore.

To the court, he was a case number: 15-4821. One count of insurance fraud. One count of forgery. One count of obstruction. To the girl in the raincoat, he was everything.

He sat at the defense table in a cheap navy suit that didn’t quite fit, the kind you get off the rack at a discount store on Memphis Avenue. His hands were cuffed in front of him, resting on a stack of papers he probably couldn’t afford to have copied. His shoulders slumped like he’d been carrying something heavy for a long time and had finally run out of places to set it down.

The prosecutor, Walters, showed the jury neat charts and grainy photocopies. He called Darius a “fraudster,” a man who “knew exactly what he was doing” when he falsified documents and misled investigators.

The facts, laid out on paper, were simple. A neighbor, Mr. Harris, had fallen behind on his mortgage. The bank moved to foreclose. Darius, who worked days as a janitor at the hospital and nights delivering for a pizza place, tried to help. He altered a letter. Changed dates. Fudged numbers. Lied to a claims adjuster.

He didn’t profit personally. The house eventually went to the bank anyway, then got sold again at a tidy profit you could see in the county records.

On paper, it was a crime. In my courtroom, crimes had consequences. Walters wanted fifteen years. “We must send a message,” he said, pounding the lectern with his hand. “If people think they can lie to banks and insurance companies whenever they feel desperate, the system falls apart.”

I’d heard that speech, in one form or another, for three decades. I had no reason to expect anything different on that March morning, with Lake Erie wind rattling the courthouse windows and gray light filtering through dirty glass.

Then the child’s voice cut across the room.

“Excuse me,” it said. “Judge?”

Every head turned.

She couldn’t have been more than seven. Two long braids framed her face, rubber bands at the ends. Her raincoat was too big for her, yellow with little ducks on the sleeves, raindrops still beading on the shoulders. Her feet, in worn pink sneakers, squeaked on the marble as she walked straight past the bailiff and up the center aisle like she belonged there.

The bailiff, Murphy, stepped forward, hand out. “Sweetheart, you can’t—”

“Bailiff,” I said, and my voice sounded different to my own ears, “let her approach.”

Murphy hesitated, then moved back.

She came right up to the rail in front of the bench, craned her head all the way back, and met my eyes without blinking.

“I’m Hope,” she said. “I’m seven. He’s my dad.”

She pointed at Darius.

In the back row, an older woman in a blue church dress—later I would learn she was the grandmother—half rose, face pale. “Hope, honey—”

Hope ignored her.

“Let my dad go,” she said, voice shaking but loud enough to fill the room, “and I’ll make you walk again.”

A beat of stunned silence. Then a low ripple of laughter. Even the court reporter, who’d seen more than most, hid a smile behind her screen.

Miracles are not on the docket in a place like this.

I didn’t laugh.

Hope’s big brown eyes flicked down to my wheelchair and back up. She saw only a problem to solve.

“Miss… Hope,” I said slowly. “Do you know where you are right now?”

“In your room,” she said. “The judge room.”

A couple of jurors smiled.

“My grandma says you’re the boss in here,” she went on. “She says you’re the one who decides if my dad has to go away. My teacher says sometimes judges don’t know everything. So I came to tell you.” She sucked in a breath. “My daddy is good. He made a big mistake, but he’s good. Please don’t take him.”

“And the legs?” I asked, before I could stop myself. “What did you mean about giving me your legs?”

She shifted her weight from foot to foot, suddenly shy. “You can’t walk,” she said matter-of-factly. “Everybody says so. My grandma says when people lose stuff, sometimes other people can help them. I still have my legs. I could give you mine. Then you could walk and you wouldn’t be so mad all the time, and then maybe you’d let my dad come home.”

Somebody in the gallery snorted. Walters rolled his eyes. “Your Honor, with respect—”

“Not now, Mr. Walters,” I said.

I should have shut it down. I should have told Murphy to escort the child back to her grandmother, reminded everyone this was a court of law, not Sunday school. There are rules about these things. Rules meant to keep emotion from drowning reason.

But my hands had gone damp on the worn wood of the bench.

Ten years I’d been in that chair. Ten years hearing people tell me to “keep hope alive” while they walked out of rooms I would never leave without help. Ten years of physical therapists begging me to stand, of harnesses and braces and the humiliation of collapsing into padded mats. Ten years of surgeries, injections, and pain that clawed up from nowhere and everywhere.

Somewhere along the line, it wasn’t just my legs that had gone numb.

Now here was a child named Hope who apparently had not gotten the memo that some things are impossible.

“You don’t believe me,” she said, softer. “But my daddy says sometimes people just need one person to believe they can do something again.”

Behind her, Darius sat up straighter. His cuffed hands tightened on the table.

“What are you asking me to do, Hope?” I said.

She swallowed. “Look at my daddy like you’d want somebody to look at you if you made one big mistake,” she said. “And then… just try.”

The prosecutor cleared his throat loudly. “Your Honor, we object to this—”

“Sit down, Mr. Walters,” I said, sharper than I intended. “You’ll have your chance to speak.”

He sank back into his chair, lips pressed thin.

I looked at Hope. I looked at the man sitting at the defense table, at the file I thought I had already decided.

And I felt it.

Yo Make również polubił

Oto jak sprawić, by pelargonie były pełne kwiatów: musisz je podlewać w ten sposób, aby zawsze dobrze rosły

Lemoniada ananasowa z cytryną

Gospodarstwa drobiu Milo ogłaszają ogólnokrajowe wycofanie jaj z powodu epidemii salmonelli

Przepis na domowy ser