Not a miracle, not some sudden flood of sensation, not the clean, sharp before-and-after of a Hallmark movie. Just a faint awareness, like the distant hum of electricity in old courthouse walls. A tingling at the top of my thighs where flesh met metal.

For the first time in a decade, I was aware of the weight of my own body.

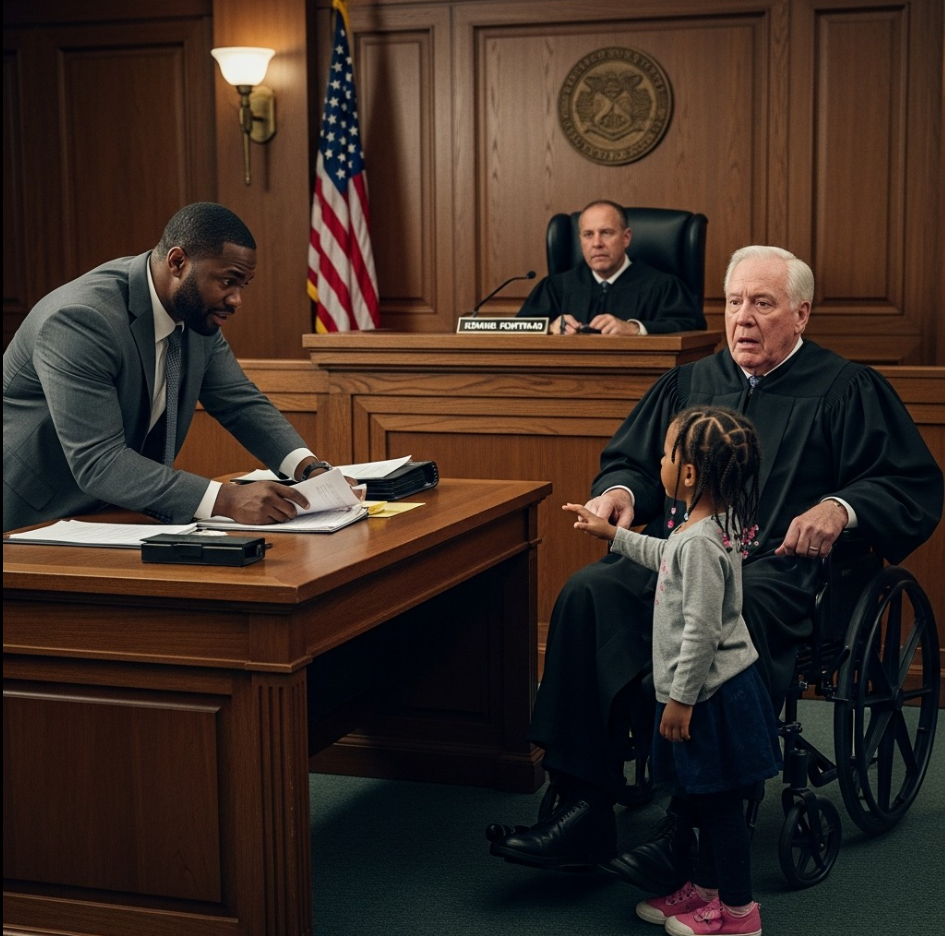

“Court will take a ten-minute recess,” I said. My voice sounded rough. “Jury, do not discuss the case. Bailiff, return the defendant. Someone please escort Miss Moore back to her seat.”

I banged the gavel before anyone could argue.

The room exploded into motion.

Murphy guided Hope gently back to the gallery. The grandmother clutched her, whispering fiercely in her ear. Jurors filed out, shuffling toward their room, casting quick, curious glances at me. Walters muttered to his second chair. Darius was led through the side door, chains rattling softly.

When the room emptied, only Diane and I remained.

She looked up from her keyboard. “You’re pale,” she said. “Do you need paramedics?”

“What I need,” I said slowly, “is for you to come around here. In case I’m about to do something very stupid.”

Her eyes widened, but she stood, pushed through the small gate in the bar, and came over to my side of the bench. Close up, I could see my own reflection in her glasses—older than I felt in my head, lines carved deeper by a decade of pain and a career of hard sentences.

“Ray,” she said quietly, dropping the “Your Honor” the way she only did when we were alone. “What are you doing?”

“Something I haven’t done in ten years,” I said.

I locked the wheels of my chair. Planted my palms on the smooth wood arms. Took a breath so deep it made my ribs ache.

The last time I’d tried to stand, a therapist named Kevin had stood two inches from my face, eyes earnest. “You’ve got this, Judge. Just lean forward. Trust the harness.” Then there had been sweat, grunts, a spike of pain, and the hot, familiar flush of humiliation when my legs refused to do anything but hang there like dead weight.

After that day, I’d told myself I was being realistic. Told the doctors I wasn’t interested in “false hope.” Told Diane it was better to focus on the facts: my spinal cord had been damaged; the odds were against meaningful recovery; chasing miracles was for other people.

But that was only half the truth.

The other half was that trying and failing hurt more than not trying at all.

Now, in the echoing quiet of Courtroom 12B, with the faint smell of coffee and wool coats still hanging in the air, I pushed.

At first, nothing happened. My arms shook with the effort. My shoulders burned.

Then—there.

A tiny shift.

The faintest engagement of muscles long thought retired. A buzzing awareness in my thighs, like someone had run a weak electric current through them.

My right foot scraped against the footrest with a sound that might as well have been thunder.

“Ray,” Diane breathed. “Stop. You’re going to hurt yourself.”

I sagged back into the chair, gasping. Sweat prickled at my temples.

“That,” I said, voice hoarse, “is the most I’ve felt in ten years.”

She knelt beside me, hand light on my arm. “Bodies change,” she said. “Nerves surprise us. But you don’t have to do this in here, now. Call Dr. Patel. Go to the rehab center. Not in the middle of a sentencing.”

“I know,” I said. “I will. But I needed to know if there was anything left to meet that girl’s courage halfway.”

She studied my face. “There is,” she said softly. “So now we deal with it.”

By the time the jury reentered, I’d toweled off, adjusted my tie, and pulled my face back into its usual neutral lines.

But inside, something had shifted.

“Back on the record in State of Ohio versus Darius Moore,” I said. “Has the jury reached a verdict?”

They had. Guilty on all counts.

Darius stood there, shoulders squared, accepting it like a man who’d expected nothing better.

“Sentencing,” I said, “is left to the Court’s discretion within the statutory range.”

Walters stepped forward. “Your Honor, the state renews its request for fifteen years’ incarceration. Anything less would send the wrong message—”

“Sit,” I said. “We’re past the part where speeches impress me.”

His mouth snapped shut.

I looked down at the pages in front of me. The pre-sentence report, the financial records, the police reports, the letters from the community. The note from his supervisor at the hospital describing him as “reliable and hardworking, always first to take an extra shift.” The teacher’s letter about him showing up at every parent-teacher conference for Hope, sometimes still in his janitor’s uniform.

Then I looked at him. Not as a file. As a man. Tired eyes. Calloused hands. A cheap tie knotted carefully.

And I thought of the way Hope had stood there, offering everything she had for a shot at him walking back out of that room with her.

“Mr. Moore,” I said. “Please stand.”

He pushed himself to his feet, chains clinking softly.

“You have pled guilty to serious offenses,” I said. “You altered documents. You lied to investigators. You interfered in a lawful process. You thought you were helping your neighbor. Maybe you were. But you chose to do it in a way that broke the law and put the integrity of the system at risk.”

He nodded once, throat working.

“The law gives me a wide range today,” I said. “I have, as has been pointed out, sent men away for long stretches for less. The question is not whether you are guilty. You are. The question is what purpose a lengthy prison sentence would serve in your case.”

I let that hang there.

“In deciding that,” I went on, “it would be irresponsible of me to pretend I did not see your daughter in this courtroom. She will live with the consequences of your choices and mine.”

Walters shifted, ready to object. I held up a hand.

“I am not saying her plea changes the law,” I said. “The law is the law. But the law allows for mercy within its bounds.”

A murmur rippled through the gallery.

“I am sentencing you to fifteen years in the custody of the Ohio Department of Rehabilitation and Correction,” I said. I heard Hope’s sharp inhale behind me. “However, I am suspending that sentence on the following conditions: five years of supervised probation, eight hundred hours of community service with an organization approved by the probation department—preferably one that assists families facing foreclosure and financial hardship—full cooperation with any civil proceedings related to this case, and no further violations of the law. You will pay the court costs. You will attend financial counseling. If you violate these terms, I will not hesitate to impose the full fifteen years.”

I paused, let the meaning sink in.

“Do you understand these conditions, Mr. Moore?”

“Yes, Your Honor,” he said. His voice broke on the last word. “Yes, sir. I… thank you.”

“Don’t thank me,” I said. “Thank the people who still believe you’re more than the worst thing you’ve done. Prove them right. Because if you come back here on another fraud charge, I promise you I will not be in such a generous mood.”

The bailiff stepped forward to remove the cuffs. Walters looked like he’d bitten into a lemon. Chavez, the overworked public defender, blinked rapidly, then pressed her lips together to keep them from trembling.

From the back, Hope’s voice rang out, unable to contain itself. “Daddy, you’re not going to jail!”

“Hope,” her grandmother hissed, half laughing, half crying.

The courtroom buzzed. I banged the gavel once. “Order,” I said, though my own throat felt tight. “Court is adjourned on this matter.”

As people filed out, I caught Hope’s eye. She beamed at me, then pointed deliberately at my legs and gave me a little thumbs-up, like we were teammates who’d just pulled off a play.

For the rest of the day, that look followed me from case to case.

A young man with a shoplifting charge and track marks on his arms. A grandmother accused of leaving two kids home alone while she worked the night shift at the nursing home on the west side. A probation violation that looked a lot more like “couldn’t afford the bus fare” than “chose to skip the meeting.”

The law hadn’t changed. The sentencing guidelines were the same words I’d read a thousand times.

But I had.

That night, in my condo overlooking Lake Erie, with the city lights reflected in the dark water and the sound of waves hitting the rocks below, I sat at my kitchen table and stared at my wheelchair.

I used to come home to Laura’s voice, the smell of her chicken soup, the soft clutter of books and plant pots she refused to stop buying. Now the place was tidy, quiet, and so still I could hear the refrigerator humming.

I reached for the phone.

“Dr. Patel’s office,” a receptionist said after the second ring.

“This is Judge Raymond Callahan,” I said. “I need to make an appointment. And… I’d like to talk about trying physical therapy again.”

Dr. Patel was a small woman with sharp eyes, a clipped Indian accent, and no patience for self-pity. Her office lived in a brick medical building off Euclid Avenue, the kind with a parking lot full of sedans and a lobby that always smelled faintly of hand sanitizer and burnt coffee.

“Ten years,” she said, flipping through my chart when I rolled in. “We do yearly images, we talk about pain, I suggest rehab, you decline. What changed?”

“A seven-year-old walked into my courtroom and tried to trade me her legs for her father,” I said.

She looked up over her glasses. “Most judges get fruit baskets,” she said dryly. “You get existential bargains.”

I told her about the tingling, about the feeling of weight shifting, about standing enough to scare myself and my clerk. I did not tell her how much I hated hearing my own voice shake in front of Diane. Some things a man keeps.

Dr. Patel listened, pen tapping against her notepad.

“Nerves are stubborn,” she said when I finished. “They die slowly. They also sometimes wake up late. We’ve seen cases where rehabilitation years after an injury yields improvements we didn’t expect. That doesn’t mean you’ll be running marathons.”

“I’d settle for getting out of this chair and scaring the daylights out of a prosecutor or two,” I said.

Her mouth twitched. “Then we start like we should have started years ago,” she said. “New imaging. Updated studies. I want you working with a therapist who won’t let you talk your way out of the hard parts.”

“Is there any chance this is all in my head?” I asked.

“Ray,” she said, “everything you experience is in your head. That’s where your brain lives. But I don’t think you’re imagining this. I think your body is offering you an opening, and for once, you’re listening.”

She scribbled an order. “Twice a week, minimum. More if we can swing it. And be prepared to be humbled.”

“I’m a judge,” I said. “Humbled is not our default setting.”

“Then it’s about time,” she replied.

Yo Make również polubił

Nie byłem tego świadomy

Naukowcy odkryli intrygującą przyczynę tajemniczej epidemii udarów u „zdrowych” młodych ludzi

Jakie są przyczyny bielactwa?

Cordon bleu z bakłażana: szybki i łatwy przepis na smażenie i pieczenie