Koperta drżała w moich zniszczonych dłoniach, gdy siedziałem w sali sądowej, patrząc, jak moja córka Rachel poprawia swój designerski żakiet z tą samą wyrachowaną precyzją, z jaką piętnaście lat temu odchodziła od swoich dzieci. Skóra ławki wrzynała mi się w tył nóg. Gdzieś za mną stary zegar sądowy tykał, jakby odliczał czas do czegoś, czego nikt z nas nie mógł cofnąć.

W wieku sześćdziesięciu dwóch lat człowiek uczy się dostrzegać ciężar pewnych chwil. Narodzin. Śmierci. Pierwszego momentu, kiedy podpisuje się pod kredytem hipotecznym. Ostatniego momentu, kiedy mówi się „kocham cię” komuś, kto już w połowie odszedł. Ta chwila – ten poranek – należała do tej kategorii. Czułem ją w kościach, w artretyzmie, który zaatakował moje palce, w bólu u podstawy kręgosłupa po zbyt wielu nocach spędzonych na szpitalnych krzesłach.

Koperta manilowa na moich kolanach wyglądała zwyczajnie. Rogi zmiękły od lat, a klapka starannie zamykana była więcej razy, niż mógłbym zliczyć. Trzymałem ją przez konferencje szkolne i uroczystości ukończenia szkoły, przez noce, kiedy chłopcy, których kochałem bardziej niż własny oddech, budzili się z płaczem za matką, która zniknęła jak mgła. Moje palce tak często obrysowywały jej krawędzie w ciemności, że tektura niemal lśniła tam, gdzie moje kciuki ją wygładzały.

Teraz siedziała między moimi dłońmi niczym mała, cicha bomba.

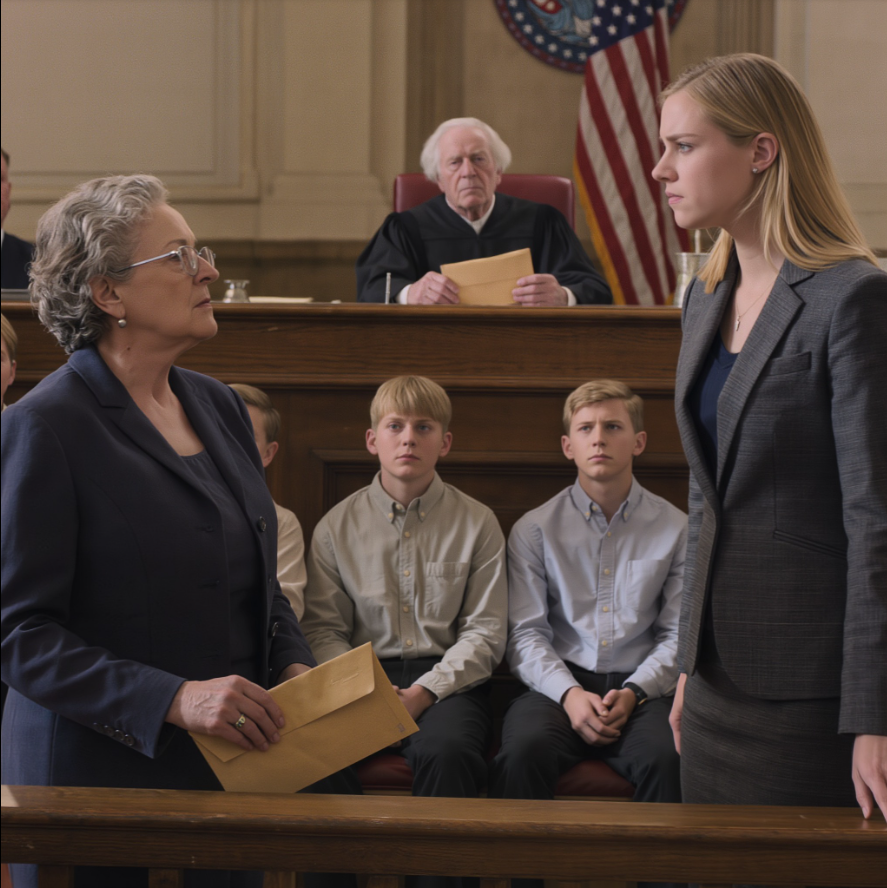

„Wysoki Sądzie” – zaczął adwokat Rachel, głosem gładkim jak jedwab po rozbitym szkle – „mojej klientce od piętnastu lat odmawia się dostępu do własnych dzieci. Domaga się natychmiastowej opieki i wnosi oskarżenie o porwanie przeciwko oskarżonej – swojej matce”.

Porwanie.

Słowo to zgrzytało mi zębami, metaliczne i niestosowne. Poczułem smak rdzy i starych monet. Zacisnąłem usta, aż przestały drżeć, i skupiłem się na słojach drewna stołu przede mną – cienkich, bladych liniach biegnących w równych rzędach. Ława sędziowska była podwyższona, a jego krzesło wytarte w poręczach, gdzie inne dłonie chwyciły go w inne burze.

„Porwanie” – powtórzył prawnik dla podkreślenia. „Babcia bezprawnie ukrywająca trójkę małoletnich dzieci przed własną matką”.

W sali sądowej było za jasno. Nad głowami brzęczały jarzeniówki, spłaszczając twarze wszystkich do postaci, które można by zobaczyć na zdjęciu z wydziału komunikacji. Czułem zapach wosku do podłóg, tonera do drukarki i stęchłej kawy, którą komornik postawił na stoliku. Gdzieś zatrzeszczał wentylator. W pierwszym rzędzie młoda kobieta z lokalnej gazety stukała długopisem o notes, a jej wzrok przeskakiwał między Rachel a mną, jakby już pisała w myślach nagłówek.

Byłam już w takich pokojach. Najpierw na przesłuchaniu mojego męża w sprawie wyjazdu na misję, kiedy byliśmy młodzi i głupi, myśląc, że wojny zawsze kończą się paradami. Potem na odczytaniu jego testamentu, po tym jak pijany kierowca uczynił mnie wdową przed czterdziestymi piątymi urodzinami. Później na papierkowej robocie, kiedy Rachel przyniosła trójkę maluchów pod moje drzwi z notatką: „Mamo, potrzebuję tylko trochę czasu”.

Ale to było coś innego.

„Pani Brown” – powiedział sędzia, przyciągając moją uwagę. Sędzia Morrison – siwe włosy, głębokie zmarszczki na czole, ciężkie zmęczenie człowieka, który doświadczył wszelkiego rodzaju ludzkiego okrucieństwa, a mimo to wstawał każdego ranka, żeby to robić od nowa. „Rozumie pani istotę tych zarzutów?”

„Tak, Wasza Wysokość” – powiedziałem. Mój głos mnie zaskoczył. Spodziewałem się, że załamie się. Nie załamał. Brzmiał równo, płasko jak rzeka Willamette w bezwietrzny dzień.

Za Rachel moi chłopcy – moi wnukowie – siedzieli razem na twardej drewnianej ławce zarezerwowanej dla rodziny. Teraz siedemnastolatkowie. Już nie chłopcy, właściwie nie. Daniel pośrodku, z zaciśniętą szczęką, ramionami zbyt szerokimi w stosunku do marynarki, którą pożyczył od sąsiada. Marcus po prawej, z dłońmi splecionymi tak mocno, że aż bielały mu kostki na tle brązowej skóry. David po lewej, z oczami wbitymi w zniszczony dywan, jakby chciał wywiercić w nim dziurę i zniknąć.

Byli wystarczająco blisko, by się dotknąć, gdyby tylko do siebie dosięgnęli. Nie dosięgnęli. Siedzieli w ostrożnej ciszy dzieci, które wcześnie nauczyły się, że burze w życiu dorosłych mogą porwać człowieka, jeśli ruszy się w nieodpowiednim momencie.

Jeszcze nie wiedzieli o kopercie. Nie wiedzieli, co zbierałem przez piętnaście lat.

„Proszę kontynuować” – powiedział sędzia.

Prawnik Rachel wstał, wygładzając krawat. Miał w sobie tę pewność siebie, której uczą się ludzie w drogich garniturach na studiach prawniczych. „Wysoki Sądzie, piętnaście lat temu moja klientka doświadczyła kryzysu psychicznego – depresji poporodowej pogłębionej przez nadużywanie substancji psychoaktywnych. Zwróciła się o pomoc. Zamiast wsparcia, jej matka w efekcie zabrała jej dzieci i od tamtej pory nie chce się ich pozbyć. W tym czasie moja klientka odbudowała swoje życie. Jest w trakcie rekonwalescencji. Jest stabilna. Jest żoną odnoszącego sukcesy profesjonalisty, ma zapewnione mieszkanie i jest gotowa odzyskać należne jej miejsce jako rodzica sprawującego opiekę nad dzieckiem”.

Jego słowa odbijały się od ścian, powtarzane i wyćwiczone.

Postpartum depression. As if that phrase explained three tiny pairs of shoes lined up by a door that never opened again. As if it covered nights when three toddlers cried themselves hoarse, cheeks flushed, clutching blankets that still smelled faintly like the mother who’d left. As if it erased the way they used to stash crackers under their beds “just in case” because somewhere their little brains had absorbed the idea that one day everything might disappear again.

“Mrs. Brown,” the judge said, turning to me. “How long have the children been in your care?”

“Since they were three, your honor.” I swallowed. “They came to stay for the weekend. They never went back.”

“By agreement?”

“At first,” I said. “Rachel said she needed a break. She was overwhelmed. I told her it was temporary.” I looked down at my hands. “It stopped being temporary when she stopped coming.”

“And during this time, the mother had no contact?”

I glanced at Rachel. Even now, at thirty-eight, she was beautiful in a way that made strangers lean in without realizing they were moving. High cheekbones, thick dark hair pulled back in a polished twist, lipstick the color of fresh berries. A small diamond glittered at her throat. She wore a cream blazer that probably cost more than my monthly grocery bill. Sitting there, she looked like the picture of success: the kind of woman other mothers at PTA meetings envied.

It had taken me years to learn that beauty can be a sort of armor. People forgive a lot if it comes wrapped in the right packaging.

“She visited twice,” I said quietly. “Once when they were eight. Once when they were twelve.”

The lawyer pounced. “And why so little contact, in your opinion?”

“In my opinion,” I said, “you’d have to ask her.”

Judge Morrison’s mouth twitched, just a bit. “Answer the question to the best of your ability, Mrs. Brown.”

“The first time,” I said, “she asked for money. She stayed the afternoon, took pictures with them at the park, told them she was coming back the next day. She didn’t. The second time, she stayed for three days, said she wanted to ‘try again’ at being a mom. On the fourth morning, I woke up to three boys crying at the kitchen table and a note that said, I’m sorry. I can’t.”

Silence snapped tight around those words.

Rachel shifted, and I saw something flash across her face—shame, maybe, or fear—before her features smoothed back into the carefully neutral mask her lawyer had probably coached into her.

“My client was in treatment,” the lawyer said quickly. “She needed time to heal. That does not negate her parental rights.”

“Rights are one thing,” the judge said evenly. “Reality is another.”

He turned back to me. “Mrs. Brown, do you have documentation of your guardianship?”

Here it was. The moment the envelope had been waiting for.

“I do, your honor,” I said, my knees protesting as I rose. The wood floor creaked under my sensible shoes. “But I’d like to present something else first.”

I walked to the front of the courtroom, aware of Rachel’s gaze burning between my shoulder blades like a brand. The manila envelope felt lighter than it had in years—maybe because I’d finally accepted it was never meant to belong only to me.

The judge held out his hand. Up close, he looked tired but not unkind. “What is this?” he asked.

“Proof,” I said. “Of what a mother really is.”

His eyebrows lifted. He opened the envelope and pulled out the first photo: Daniel on his first day of kindergarten, hair sticking up in three directions because he’d been too excited to sit still long enough for me to fix it. He was grinning, missing his two front teeth, clutching a Spider-Man lunchbox we’d picked out at Goodwill. I’d forgotten a jacket that morning and shivered the whole walk home, but it didn’t matter. He’d gone in smiling.

The judge looked at the picture a moment longer than he needed to. Then he pulled out the next: Marcus receiving his first-place ribbon at the third-grade science fair, eyes shining as bright as the little foil sticker on his project board. David, age seven, wobbling on his bike without training wheels, frozen mid-victory whoop as I snapped the photo with my old phone.

It wasn’t just pictures. The judge reached in and found report cards, each one slipped carefully into a plastic sleeve to protect it from spilled juice and the chaos of daily life. Teacher notes: David is excelling in math. Marcus shows empathy beyond his years. Daniel is a natural leader—channel that energy!

There were permission slips for field trips signed in my neat, looping handwriting. Emergency contact forms listing my number above the words Call first, then Mom if no answer—a line I’d written because I couldn’t quite bring myself to erase Rachel’s name entirely. Medical records showing me as the authorized guardian and consent giver. Copies of the original paperwork that allowed me to enroll them in school when Rachel “needed time to think” in another city.

Rachel’s lawyer shifted in his seat. “Your honor, we object to—”

“Sit down,” Judge Morrison said, not raising his voice but sharpening it. The lawyer sat.

“How long did you compile this?” the judge asked.

“Fifteen years,” I said. “Every time a form asked for a parent signature, I signed. Every time a nurse needed someone at two in the morning to authorize a breathing treatment, I went. Every open house, every parent-teacher conference, every summer school enrollment. If there was a line for ‘guardian,’ my name went on it.”

“And the mother’s name appears how often in these documents?” the judge asked.

“Never, your honor,” I said softly. “Not once.”

One of my boys made a small sound behind me—something between a gasp and a sigh. I didn’t turn around. I couldn’t. Not yet.

The judge leafed through the stack. He paused on a particular photograph, and even from where I stood, I knew which one it was: the three of them at ten, standing in front of our small artificial Christmas tree in my cramped Portland apartment. The tree leaned slightly to the left because one of the legs was missing and I’d propped it up with an old phone book. The boys wore matching pajamas I’d sewn from fabric I found in a clearance bin: misprinted reindeer heads and snowflakes that didn’t quite line up.

Their faces, though, were perfect—eyes bright, cheeks flushed, arms slung around each other like they were three parts of the same whole.

“Where were you when this was taken?” the judge asked, turning to Rachel.

Her throat worked. “I… I don’t remember,” she said. Her voice, always so smooth on the phone when she needed something, cracked on the last word. “I was getting my life together. I couldn’t—”

“You couldn’t call?” the judge asked. Again, his tone stayed calm. That made it worse. “Send a card? Ask someone how your children were?”

Tears filled Rachel’s eyes. For a second, she looked like the twenty-three-year-old who’d called me from a bathroom stall at two in the morning, voice shaking as she stared at two pink lines on a pregnancy test. My heart clenched, traitorously. Then I remembered the way three small bodies had curled together on our pull-out couch, asking over and over, “Did Mommy forget us?”

“Mrs. Brown,” the judge said, bringing me back, “is there anything else in this envelope?”

“Yes, your honor.” My fingers squeezed the edges of the file. “The school records. Every form that required a parent or guardian. Every emergency contact sheet. Every authorization for medical care. Every notice of delinquent lunch fees I paid off in installments when I was short on cash.”

He pulled out a thick stack of papers, flipping through them slowly. My name, over and over again. Sometimes neat, sometimes hurried, sometimes a little smudged where a kid had bumped my elbow at the kitchen table.

The judge set the stack down carefully, as if it weighed more than paper. In a way, it did. It weighed fifteen years of showing up.

He looked at me. “Do your grandsons know what’s in this envelope?”

“Not yet,” I said.

“Why not?”

“Because some truths are too heavy for children to carry,” I said. “Even when those children are almost grown. Because I wanted them to have the chance to know their mother without my bitterness staining every memory. Because I didn’t want them to look at every missed birthday, every silent Christmas, every empty seat at a school play and see a legal strategy—they deserved to feel their emotions before they understood her motives.”

“You believe they’re ready now?” the judge asked.

I thought of Daniel wincing when people called me “Mom” by mistake and then correcting them with “She’s my grandma, actually,” like there was honor in the technical truth. Of Marcus, who still checked the porch twice on his own birthday, as if maybe this would be the year a mother appeared with balloons. Of David, whose stomach knotted before parent-teacher conferences because he was afraid every adult conversation meant someone might be leaving again.

“Yes,” I said. “They’re old enough to hear the truth. And to decide what they want to do with it.”

The judge leaned back, exhaling slowly. I could almost see the decision solidifying in his mind. Before he could speak, Rachel stood.

“I made mistakes,” she said. Her voice was thick with tears. “I was young. I was sick. But they’re still my children. I gave birth to them. I love them.”

I turned to look at her, really look at her. For a heartbeat, I saw my little girl again—the one who used to fall asleep across my lap in front of the TV, the one who’d insisted on reading to my belly when she was five and I was pregnant with her baby brother, the teenager who’d promised she’d do better than I had.

“Love isn’t just a feeling,” I said quietly. “It’s a choice you make every day. At three in the morning. On the bad days. When no one’s watching.”

“Mrs. Brown,” the judge said gently, “step back, please. I need to speak with the boys.”

My heart hammered against my ribs as I returned to my seat. The wooden bench felt harder than before. Daniel, Marcus, and David stood and walked to the front of the courtroom together, shoulders almost touching.

Up close, they looked like variations on a theme: their father’s dark eyes, his stubborn jaw, the same dimple in their left cheeks when they smiled. I could see bits of myself too—the way they squared their shoulders when afraid, the crease between their brows when they were thinking hard.

“Gentlemen,” the judge said, and his voice softened in a way it hadn’t when speaking to the adults, “I know this is difficult. But I need to ask you something directly. Do you want to live with your mother?”

The air thinned. The fluorescent hum, the scratch of pens, the creak of leather—all of it disappeared. We were suspended in silence, hanging over the edge of something none of us could climb back from.

Daniel, always the spokesman, cleared his throat. “Your honor,” he said, and his voice had dropped an octave since the last time I’d really listened to it, “we don’t really know her.”

Those six words landed with the weight of a verdict.

Rachel flinched. Her lawyer closed his eyes briefly, like a boxer taking a hit he’d seen coming but couldn’t dodge.

Yo Make również polubił

Postaw puszkę tuńczyka za telewizorem, a wszyscy będą zaskoczeni efektem!

Produkty spożywcze, których należy unikać, aby zapobiec atakowi dny moczanowej

Naturalne sposoby zapobiegania próchnicy i wzmacniania zębów

4 naturalne sposoby, które naprawdę pomagają spać przez 8 godzin