Physical therapy was fluorescent lights, rubber mats, and the smell of sweat and disinfectant. The rehab gym hummed with the whir of machines and the soft groans of people trying to make their bodies obey.

My therapist, Jorge, was in his thirties, with kind eyes and forearms like tree trunks. He had a talent for ignoring my sarcasm.

“First day,” he said, wheeling me up to a set of parallel bars. “We’re not going to make you run a 5K. We’re going to remind your brain that your legs still exist.”

“They exist, all right,” I said. “They ache at three in the morning often enough.”

“Pain is a form of communication,” he said. “Annoying, but useful. Up you go.”

They strapped braces to my legs. Fitted a harness around my torso that hooked into a track in the ceiling. It took three people to stand me between those bars the first time: Jorge, an aide, and a tech who’d seen a hundred stubborn men in wheelchairs and treated me exactly like one more.

“Hands on the bars,” Jorge said. “Shift your weight forward. Don’t overthink.”

I overthought. That’s what I do.

Still, I leaned.

The buzz in my thighs lit up, more insistent than in the courtroom. My knees shook. My shoulders burned. The harness took more of my weight than I liked. Borderline humiliating.

“Good,” Jorge said, like I’d just done something impressive. “Again.”

We did it again. And again.

By the time I rolled out of there, my arms trembled and my shirt stuck to my back. It felt like I’d been put through a wringer.

It also felt like something inside me had cracked and let air in.

My days fell into a new rhythm.

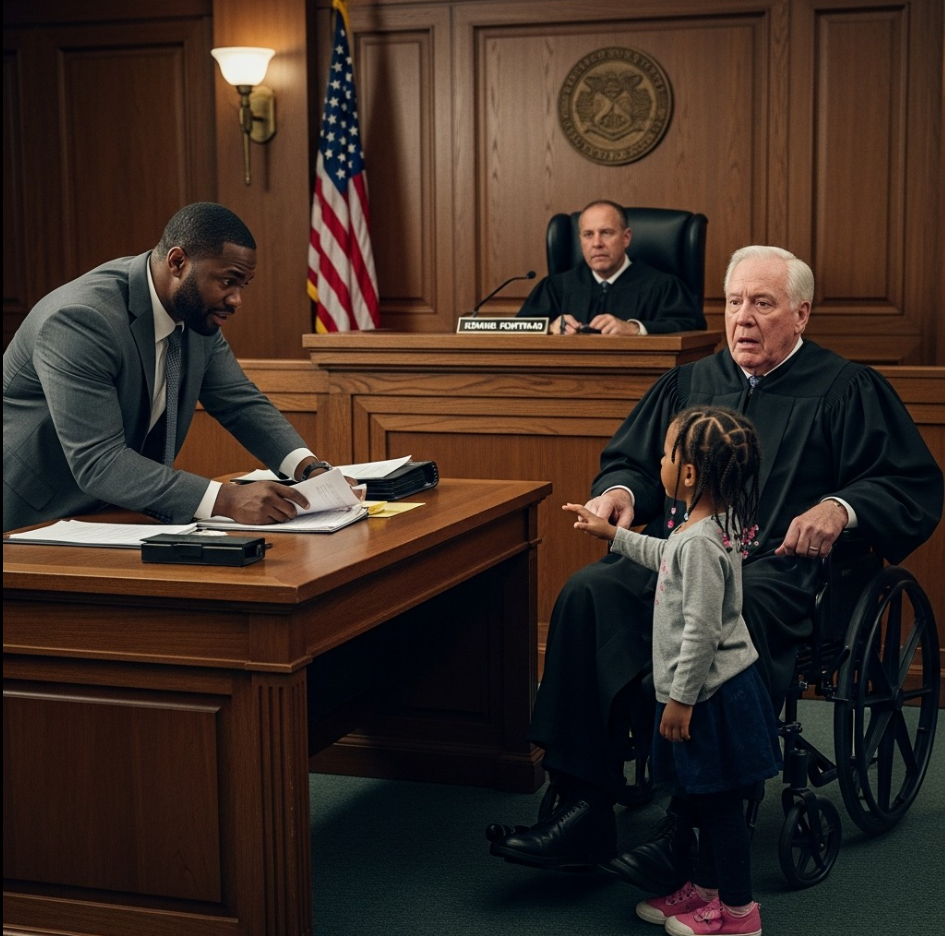

Mornings: downtown Cleveland. Justice Center. Security check, elevator ride, the wheelchair humming softly over polished stone floors. A Styrofoam cup of burnt coffee from the basement kiosk. A quick nod from Murphy. The heavy door of Courtroom 12B swinging open as the bailiff called, “All rise!” and everyone stood while I rolled in.

I saw the same types of faces I always had: scared, angry, bored, resigned. People in orange jumpsuits. People in wrinkled dress shirts. People in church clothes that smelled faintly of fabric softener and desperation.

I still read pre-sentence reports. I still listened to arguments. I still believed in boundaries and consequences.

What changed first was small.

On a petty theft case, I stopped myself from snapping when a young man tried to explain why he’d stolen diapers and formula from a grocery store. Instead, I asked one extra question: “Who’s at home with the baby?”

On a probation violation, I found myself asking the officer, “How many times has he actually missed appointments?” instead of rubber-stamping a recommendation.

On a case involving an elderly woman accused of neglect, I asked how many hours she was working at the nursing home on the night shift because Social Security wasn’t enough.

The law didn’t suddenly turn into a warm blanket. But I started seeing where it chafed people who were already raw.

Afternoons: rehab. Parallel bars. Mats. Exercises that made me feel like a baby giraffe learning to walk.

“Shift,” Jorge would say. “Good. Again.”

Little by little, I felt muscles remember. Ankles twitch. Knees quiver. Hips protest, then comply.

It was slow. It was ugly. It hurt.

It was also the first thing, outside of that courtroom, that made me feel like I was moving forward instead of being pushed.

I didn’t see Hope again for a few weeks. Cases move on. Dockets fill. People fall out of the daily parade.

Then one afternoon, as I rolled down the hallway toward my chambers, I heard a familiar voice.

“Judge!”

She barreled toward me from the waiting area, her braids flying, sneakers squeaking on the tile. Her grandmother trotted after her, breathless.

“Hope,” I said, fighting a smile and failing. “How are you?”

“Daddy has to talk to the probation man a lot,” she said. “But he comes home every night. Grandma says that’s what matters.”

“She’s right,” I said.

Hope tilted her head, taking in the wheelchair, my suit, the files in my lap. “Did you try?” she asked bluntly. “Like you said?”

Her grandmother winced. “Hope, that’s not polite.”

“It’s all right,” I said. “Yes, I tried. A man named Jorge makes me curse under my breath twice a week while he tells me I’m doing fine.”

“Does it hurt?” she asked.

“Yes,” I said. “But not as much as I thought it would. And I stood for a few seconds the other day.”

Her eyes got big. “Really?”

“Really,” I said.

She reached out and patted my knee, as if testing it. “Good,” she said. “Then the deal is working.”

“The deal?”

“You know,” she said patiently. “I give you my courage, you give me my dad.”

From anyone else, it would have sounded like a joke. From her, it sounded like a contract.

Her grandmother cleared her throat. “Your Honor, we just wanted to say thank you,” she said. “I know you hear that a lot, but… he’s working both jobs, and he’s doing those hours for Legal Aid, and… my girl here isn’t spending Saturdays in a prison visiting room.” Her voice wobbled. “That’s a gift I never thought we’d get.”

“I didn’t give it alone,” I said. “Your son did the hard part when he told the truth. Your granddaughter did the hard part when she walked up that aisle. I just did my job with my eyes a little more open than usual.”

Hope beamed. “I’m going to be in the spring concert,” she said. “Second grade. We’re singing a song about light. You should come.”

“The judge is very busy,” her grandmother said quickly.

“I’ll see what I can do,” I said.

That night, at my kitchen table with the lake dark outside the window, I opened my paper planner—a stubborn habit in a digital world—and wrote, in tiny neat letters, “Hope’s concert?” on the day she told me.

Old dogs, as it turns out, can learn more than one new trick at a time.

The first time I stood without a harness catching most of my weight, it was a Tuesday. Nothing special about it. Gray sky, drizzle turning the parking lot into a mirror.

We’d been working at this for months.

“Ready?” Jorge asked, hands on his hips.

“No,” I said. “But let’s go anyway.”

I gripped the parallel bars. My arms had gotten stronger. My shoulders still hurt, but it was a clean, working pain, not the dull ache of disuse.

“Shift forward,” he said. “Wait. There. Try to straighten.”

I pushed through a wall of fear that had lived in my chest for a decade. Muscles fired down my thighs. My knees wobbled. My heels pressed into the mat.

And then, suddenly, the chair was no longer under me.

I was standing.

No harness. No Kevin with his encouraging little nods. Just my own two feet bearing my weight while my hands clung to the bars.

“Breathe,” Jorge said. “Look up. Don’t stare at your feet. They’re not going anywhere.”

I laughed, a wild, shaky sound. The rehab gym, with its purple walls and scuffed mats and poster about fall risk, might as well have been a cathedral.

It lasted maybe five seconds. Ten. Long enough for my vision to blur and my knees to threaten mutiny. Then I sat back down, shaking and grinning like a fool.

“Again tomorrow,” Jorge said calmly, as if a man in his sixties pulling off his first stand in ten years was just another line in his notes.

On the drive home, with the wipers slapping at a slow drizzle and the radio mumbling classic rock, I felt tears prick my eyes.

Not because I’d stood.

Because a part of me that had shut down the night of the accident had finally cracked open a little.

Hope, I realized, isn’t a feeling. It’s a decision you make over and over to try again.

Word spreads in a courthouse. It’s a rumor mill with law degrees.

“Callahan’s doing PT again,” I overheard one attorney tell another at the coffee stand.

“He’s been different on the bench,” someone else said. “Still tough, but he’s asking more questions.”

“Mid-life crisis,” Walters muttered once in the hallway, loud enough for me to hear. “Just ten years late.”

I let it slide. I’d heard worse.

Inside the courtroom, changes showed up in small ways.

In a drug case, when a young man facing prison for possession with intent stood before me with a string of priors and eyes that looked older than his age, I found myself asking, “What’s actually available in terms of treatment beds right now?” instead of “Why should I believe you’ll change?”

In a case involving a shoplifting grandmother, I ordered community service at the elementary school her grandkids attended instead of six months in jail.

In a domestic violence case, I still imposed a hard sentence. There are lines I have no interest in blurring. Mercy is not the same as indulgence.

But every time I signed my name on a sentencing entry, I saw Hope in my mind’s eye, standing as straight as her seven-year-old legs would allow, asking me to look at her father like a person, not a problem.

I started looking at all of them that way.

I didn’t tell anyone about my plan the day I decided to stand up in court. Not Diane. Not Murphy. Certainly not Dr. Patel.

It was almost a year after that first hearing. Late winter again. Lake Erie doing its best impression of a gray steel plate. The docket was packed.

When I rolled into Courtroom 12B that morning, I felt the weight of what I was about to do settle on my shoulders like an extra robe.

We made it through the first few cases. A probation violation. A plea hearing. Routine.

Then I saw them in the gallery.

Second row, right side. Darius in a clean shirt and tie, hair cut, shoulders squared. Next to him, Hope in a striped dress, swinging her legs, whispering to her grandmother.

Jorge had asked me, half joking, “When are you going to show off?”

“Judges are not supposed to show off,” I’d said.

But I’d been thinking about it ever since.

On a break between cases, I cleared my throat.

“Before we proceed,” I said, “the Court is going to do something… unusual.”

Every head turned. Diane’s fingers stilled over her keyboard.

“This is not part of any official proceeding,” I said. “No one needs to note this in any record. But a year ago, in this room, a child asked me to try something I had not tried in a long time. She kept her promise. I’d like to show her that I kept mine.”

Murphy looked confused. Walters, sitting at counsel table on the next case, looked annoyed.

I rolled my chair back from the bench. The oak carved with the state seal loomed over me. The room that had been my stage for three decades felt unfamiliar.

“Diane,” I said quietly. “If I fall on my face, you are never speaking of this again.”

She swallowed. “Yes, Your Honor,” she murmured.

I locked the wheels. Planted my hands on the arms. Took a breath.

In the back row, I heard Hope whisper, “He’s gonna do it.”

I leaned forward.

Yo Make również polubił

Matka ostrzega po tym, jak jej roczny synek zgubił się w wyniku uderzenia zwykłym przedmiotem

Domowy Likier Kawowy w 5 Minut: Przepis na Wyjątkowy Napój o Smaku Baileys

Ciasto Ricotta: Przepis na super pyszny deser z kawałkami czekolady

🐽 Quiz o Nosach Zwierząt – Czy Rozpoznasz je Wszystkie? 🐾